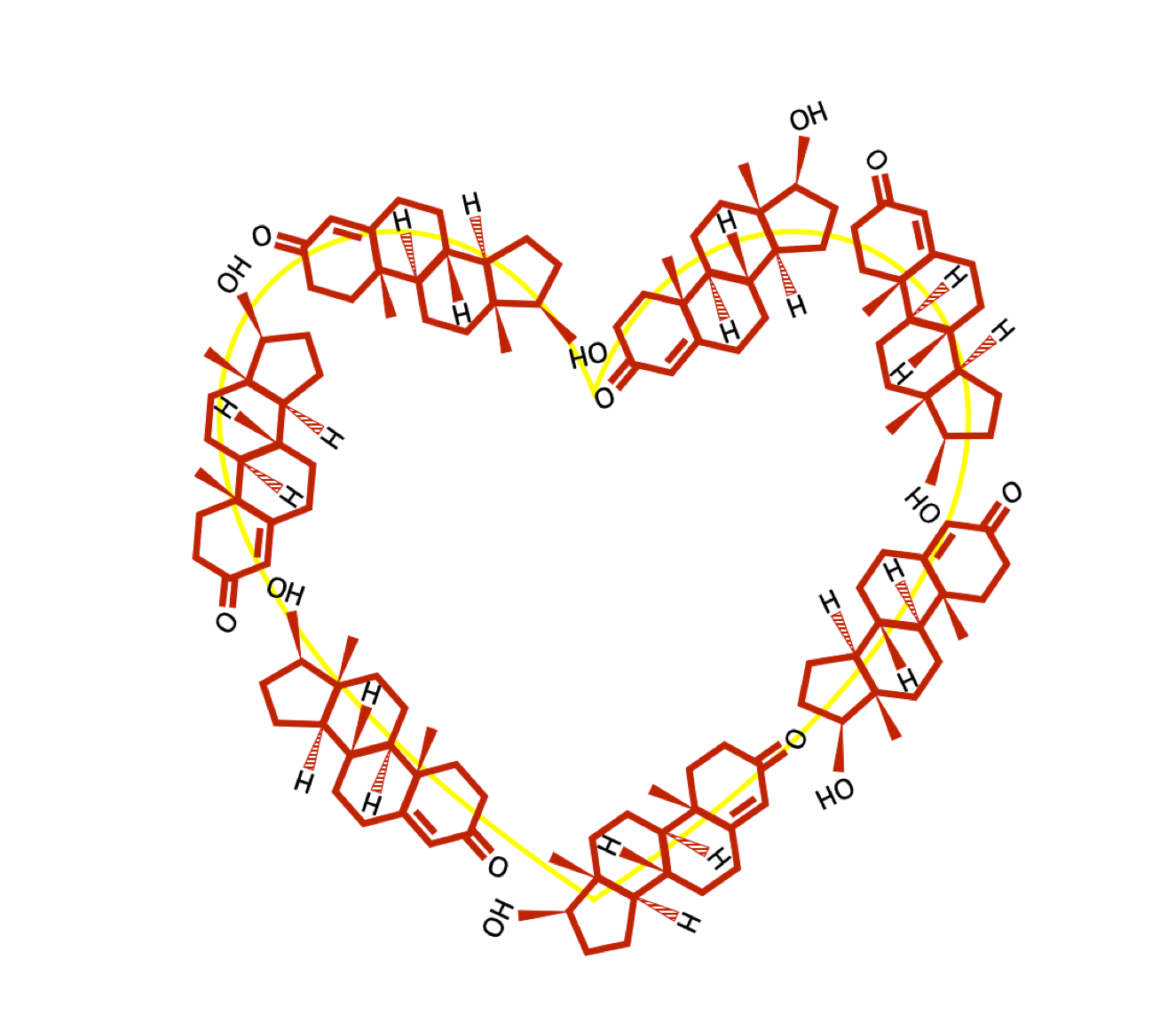

Sex hormones and athletes

For most people, sex assignment is based on the presence of external female or male genitalia at birth. Sex identification at birth usually, but not always, corresponds to genetic sex.

"Intersex" individuals born with XX or XY genes and a disorder of sex development (DSD) are often not easily identified biologically as male or female at birth and may be assigned either sex.

Some people self-identify to a gender that differs from how they biologically appeared at birth and successful and healthy living in a self-identified gender often requires taking sex hormone therapy.

Physiological effects of sex hormones on athletic performance

Testosterone therapy does not create a competitive advantage in sports for trans men compared to cis men.

However, there is controversy around whether trans women (with therapeutic testosterone suppression) or women with high testosterone concentrations (due to DSDs) have a competitive advantage in elite athletic events.

To help define their inclusion criteria, the U.S. National College Association of Athletics (NCAA) Diversity and Inclusion Committee and NCAA Committee on Competitive Safeguards and Medical Aspects of Sports recently asked a small group of researchers - including Drs. Bradley Anawalt and Alvin Matsumoto - to prepare a report summarizing what is known about the physiological effects of sex hormones on athletic performance.

Competitive advantage?

The NCAA notes that the most cited reason for resistance to transgender student athletes participating in sports is the concern over creating an unfair competitive advantage.

The researchers report that there are no biological markers that reliably predict a competitive advantage.

However, hemoglobin is the protein that carries oxygen in the blood. An increase in hemoglobin increases the amount of oxygen to the muscles, and increased hemoglobin appears to confer a competitive advantage in many sports.

"Blood doping" is therefore banned as are medications that stimulate the production of hemoglobin and red blood cells. Testosterone increases the production of hemoglobin and red blood cells.

Elevated blood testosterone concentrations may give women (and men) a competitive advantage in athletic events where muscle strength, speed, or endurance is important. There are many factors that affect testosterone effects on athletic performance, however. For example, there is variation in individual responsiveness to the effects of testosterone.

Trans females

Trans female athletes who begin hormone therapy to transition (male to female) after puberty remain taller on average than cis female athletes and have more muscle mass for more than a year after initial suppression of testosterone.

The NCAA’s current policy states:

A trans female (MTF) student-athlete being treated with testosterone suppression medication ... may continue to compete on a men’s team but may not compete on a women’s team without changing it to a mixed team status until completing one calendar year of testosterone suppression treatment.

Disorder of Sex Development (DSD)

Some of the controversy is surrounding female gender athletes (regardless of genetic sex) with naturally occurring high blood testosterone concentrations due to DSD.

These athletes have a lifetime exposure to greater amounts of testosterone than cis women without a DSD, which is associated with important physiological differences (e.g., increased muscle and red blood cell production) that may create a competitive athletic advantage.

History of gender policies in sports

The first gender policy was instituted by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) in 1946 when they required women to provide medical certificates (“Fem cards”) to prove they were female.

Subsequent methods included physical examinations (referred to as "naked parades") and chromosomal and hormonal testing.

In 2004, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) adopted the "Stockholm consensus," for athletes who had undergone sex reassignment and wanted to compete in sports.

In addition to requiring that legal recognition of gender had been conferred and hormone therapy had been administered "for a sufficient length of time to minimize gender-related advantages in sport competitions," the consensus required that "surgical anatomical changes" had been completed.

In 2011, IAAF became the first international sports federation to adopt rules and regulations governing the eligibility of females with hyperandrogenism (high natural levels of testosterone in women, aka DSD) to compete in women’s competition.

The rules stated:

A female with hyperandrogenism who is recognised as a female in law shall be eligible to compete in women’s competition in athletics provided that she has androgen levels below the male range (measured by reference to testosterone levels in serum) or, if she has androgen levels within the male range she also has an androgen resistance which means that she derives no competitive advantage from such levels.

The 2011 IAAF policy was suspended in 2015, following the Dutee Chand case where the court found that there was a lack of evidence provided that testosterone increased female athletic performance.

The IAAF claims they are trying to maintain a level playing field for all women athletes and that DSDs have testosterone that is in the male range.

They also state that the number of DSD individuals in the elite athlete population is around 140 times higher than in the general female population, and their presence on the podium is even more frequent.

"Protected class"

IAAF introduced new rules in 2018 requiring female athletes with DSDs to lower their testosterone if they want to compete internationally in events between 400m and a mile.

The 2018 rules only apply to a certain number of specified DSDs -

- Legally female (or intersex)

- Male chromosomes (XY)

- Testes not ovaries

- Circulating testosterone in the male range

- Ability to make use of that testosterone circulating within their bodies ('androgen-sensitive')

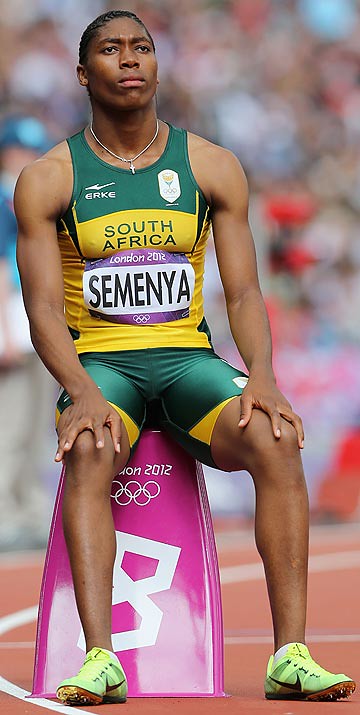

Caster Semenya, a double 800m Olympic champion from South Africa, challenged those rules, claiming the narrow scope specifically targeted her. She was previously targeted by the IAAF in 2009 when they ordered her to undergo gender testing after winning gold in the Track and Field World Championship in Berlin.

Caster Semenya, a double 800m Olympic champion from South Africa, challenged those rules, claiming the narrow scope specifically targeted her. She was previously targeted by the IAAF in 2009 when they ordered her to undergo gender testing after winning gold in the Track and Field World Championship in Berlin.

Semenya has also said she has emotional distress from being forced to take the drugs from 2011-2015 when the initial policy was in place.

Anawalt and colleagues did not comment specifically about Ms. Semenya -

"We do not (and should not) know the details of her medical information. There might be emotional distress caused by a requirement of medical therapy to compete.

But there also might be emotional distress for cis female competitors who are excluded from competition (e.g., a cis woman who does not qualify for the finals of a track event because of losing to a woman with DSD and high testosterone)."

Semenya lost her case against the IAAF in May 2019, when the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) upheld the IAAF's DSD regulations.

The CAS Panel found -

The DSD Regulations are discriminatory but that, on the basis of the evidence submitted by the parties, such discrimination is a necessary, reasonable and proportionate means of achieving the legitimate objective of ensuring fair competition in female athletics in certain events and protecting the “protected class” of female athletes in those events.

The IAAF's DSD regulations have been criticized as based on flawed data.

“Everyone wants science to provide precision," says Anawalt. "They want to know precisely how much competitive advantage is conferred by testosterone to a trans woman vs a cis woman due to lifetime exposure to testosterone, and what persists and what does not. The study cited by the IAAF attempted to quantify exactly how much competitive advantage was attributable to testosterone. It cannot be done."

Semenya is appealing the decision to the Switzerland’s Federal Supreme Court and has said:

“No woman should be subjected to these rules. I thought hard about not running the 800m in solidarity unless all women can run free. But I will run now to show the IAAF that they cannot drug us.”

The report by Anawalt and colleagues concludes that although it is not possible to determine whether very high blood concentrations of testosterone that are made (not taken) by females with DSD confers a competitive advantage in athletic performance compared to cis females without DSD, the indirect data strongly suggest it.

The NCAA notes there are many types of competitive advantages in sports: technological, environment, financial, social and genetic/physical.

"Science cannot provide a just and fair answer on how to include all individuals who self-identify and want to compete as women in athletic competitions,” says Anawalt.

The "Report on Sex Hormones and Athletes for the NCAA" was prepared by Drs. Bradley Anawalt, Richard Auchus, Alan Rogol and Alvin Matsumoto.

Dr. Bradley Anawalt is a professor of medicine at the University of Washington where he conducts research on the effects of testosterone on men, and he takes care of many transgender patients. He was one of the invited reviewers of the most recent international guidelines on the care of transgender people.

Dr. Alvin Matsumoto is a professor of medicine at the University of Washington and associate director of the Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center and director of the Clinical Research Unit at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, where he conducts research on the effects of testosterone in men.

Dr. Richard Auchus is a professor of internal medicine and pharmacology at the University of Michigan and Chief of the Endocrinology at the Ann Arbor Veteran's Affairs Health System. He conducts basic and clinical research related to steroid biosynthesis and its disorders, including those that influence sex development, and he manages these patients and transgender patients.

Dr. Alan Rogol is professor emeritus of pediatrics and pharmacology at the University of Virginia. His interests include the study of growth and adolescent development as well as the endocrinology of exercise and sport, particularly as they affect the adolescent athlete.