Immune-system signaler also appears to cause kidney injury

Interferons, part of the body’s immune system, appear to cause kidney damage most likely to affect Black people, newly published research suggests. The investigators also found that drugs approved for other conditions can thwart this detrimental side effect of interferons.

The findings appear today in the journal Cell Reports. The study’s lead author is Benjamin Juliar, a postdoctoral scholar in nephrology at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

The findings appear today in the journal Cell Reports. The study’s lead author is Benjamin Juliar, a postdoctoral scholar in nephrology at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

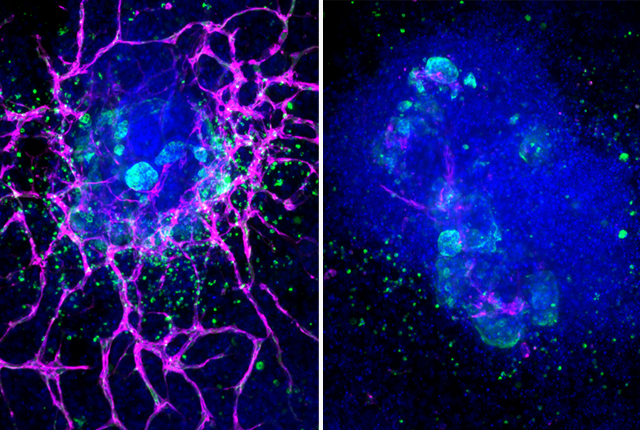

The investigators used organoids, which are grown from human stem cells and resemble miniature kidneys. These structures contain filtering cells and can respond to infection and therapeutics in ways that parallel the responses of kidneys in people.

In the experiment, the researchers examined the activity of a gene that responds to interferon and is also associated with kidney disease. This gene, called APOL1, has mutations that are common among people with African ancestry. Individuals who inherit one copy of this gene are better able to resist sleeping sickness, a deadly parasitic brain infection found in sub-Saharan Africa. Inheriting two copies, however, increases one’s risk of developing kidney disease.

“But kidney disease doesn't develop in every patient with this gene, so we think some other trigger is at work, and it's believed to be an inflammatory trigger,” said the study’s senior author, Benjamin Freedman. He is an associate professor of medicine (nephrology) at the UW School of Medicine.

“But kidney disease doesn't develop in every patient with this gene, so we think some other trigger is at work, and it's believed to be an inflammatory trigger,” said the study’s senior author, Benjamin Freedman. He is an associate professor of medicine (nephrology) at the UW School of Medicine.

“We think this isn't just some weird thing happening in a petri dish, but rather a real phenomenon happening in the cells of people with kidney disease,” said senior author Benjamin Freedman.

Interferons summon an inflammatory response from the immune system to fight new infections in a body. So Freedman and colleagues set out to scrutinize the interplay of interferon-gamma with the APOL1 gene.

“We saw in the organoids that interferon caused APOL1 levels of expression to go up. But we also noticed that the interferon itself was associated with an inflammatory form of cell death in blood vessels’ endothelial cells — even in the context of normal levels of APOL1,” Freedman said.

That, he said, is one of the paper’s two core findings.

“The model that emerges is that, in everybody, there's this detrimental effect of interferon and expression of APOL1,” he explained. “And in these patients who have the risk variants of APOL1, that's enough to cause kidney disease.”

The other core finding is that existing therapeutic compounds blocked or reduced interferon’s ability to cause endothelial cell death in the organoids. Results were most profound with ruxolitinib and baricitinib, two of nine compounds studied.

“We inhibited the signals in between the interferon and the cell death,” Freedman said. “When we block that signal preventatively, we saw a dramatic rescue, and if we block at later stages, we saw a partial rescue.”

The scientists also were able to tie the APOL1 gene-expression signatures in organoids to what they observed in tissue samples from humans with kidney disease.

“That's why we think this isn't just some weird thing happening in a petri dish, but rather a real phenomenon happening in the cells of people with kidney disease,” Freedman said.

Understanding that blood-vessels are particularly susceptible to this type of inflammatory cell death is important, he said, adding that the rescue seen in the organoids suggests that a next step might be a clinical trial that includes patients who have both kidney disease and the APOL1 gene mutation.

The research was supported by National Institutes of Health awards (R01DK130386, R01DK117914, UH3TR000504, UH3TR002158, UH3TR03288, U01DK127553, 5UC2DK126006) and Department of Defense awards (W81XWH-21-1-0006 and W81XWH-21-1-0007).