The Bruce Protocol: A 75-year legacy of innovation

Innovation in cardiology

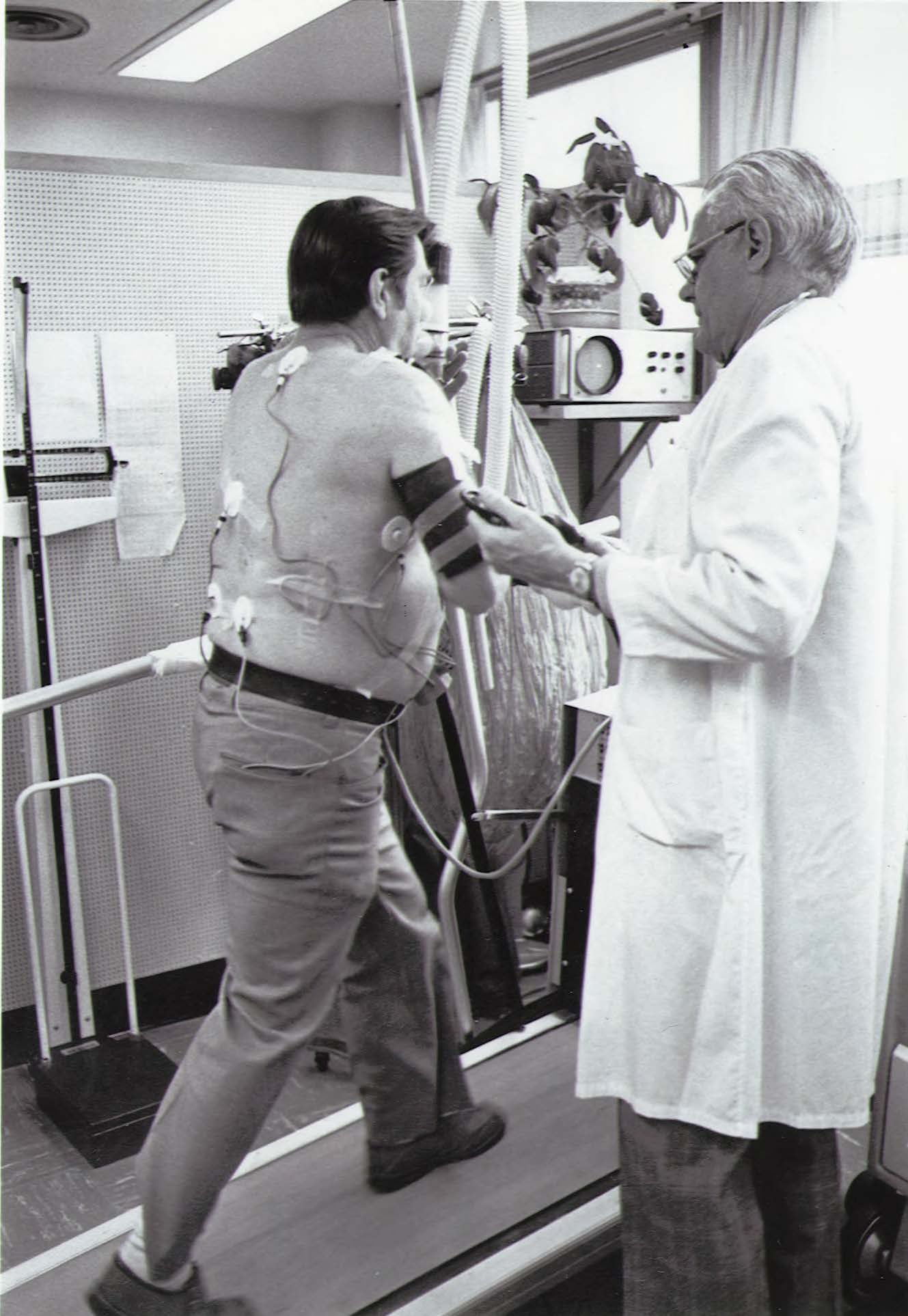

When UW Medicine cardiologist Robert A. Bruce, MD, developed his technique for evaluating cardiac function and physical fitness, it revolutionized the way clinicians assessed patients for cardiovascular disease. His method, the Bruce Protocol, opened the door for valuable advancements in cardiovascular diagnostics.

professor (Cardiology)

And 75 years after capturing the first treadmill results, it remains the foundation for exercise stress testing.

“The brilliance of his protocol was putting together the concept of provoking physiologic stress without harming the patient in order to know when to intervene,” says James Kirkpatrick, MD, FASE, FACC, director of the Echocardiology Laboratory at UW Medicine’s Heart Institute. “The subsequent work built on this method has allowed us to risk-stratify patients and develop new diagnostic technologies.”

The protocol did more than improve patient care. It also launched the Division of Cardiology down a decades-long path of innovation.

Addressing Variability in Symptoms

Kirkpatrick says the Bruce Protocol set the stage for cardiology to overcome one of the main obstacles in patient care — the variability of cardiovascular symptoms across ages, ethnicities and more. Historically, cardiologists assessed the presence of coronary artery disease based on symptoms, such as chest pain and pressure, which unfortunately is not the way many patients present, particularly women.

Being able to pair quantifiable, real-time data with a patient’s description of what they’re feeling made a difference in assessing individuals and creating care plans.

“The idea that you could take something so intrinsically variable and use a non-invasive test to recognize differences was game-changing,” he says. “We’re now much better able to define what’s going on in any patient, regardless of who they are. We can get rid of a lot of variability that exists between people, their perceptions, their ways of explaining things and what they’re feeling.”

A Flourishing Division

The advent of the Bruce Protocol made it easier to evaluate patients. By incorporating electrocardiogram (ECG) measurements into the stress test protocol in a standardized way helped detect heart artery blockages and also heart rhythm disturbances that happen during exercise. As such, it paved the way for continued growth, expansion and advancement in the field of cardiology and in the Division of Cardiology at the University of Washington, in particular.

Ultimately, as the home of the Bruce Protocol, the UW Medicine Division of Cardiology has helped shape the face of modern stress testing and cardiovascular diagnostics. And there is still room for more innovation.

“Part of the legacy of the Bruce Protocol is that we’ve gotten better at figuring out who needs invasive testing in cardiology,” Kirkpatrick says. “This protocol was a great foundation, and we use it every day. But we certainly haven’t rested on our laurels.”

Today, the division operates a thriving, robust stress department within the echo cardiology lab that sits next to the cardiology clinic at all UW Medicine sites. Specially trained nurses and ECG technicians administer these tests which can be paired with heart ultrasound or nuclear medicine imaging for improved detection of heart problems.

Over the decades, uses for the Bruce Protocol have expanded. Now, Kirkpatrick says UW Medicine cardiologists pair these technologies and techniques to detect:

- Causes of shortness of breath

- Stiffening of the heart muscle

- Problems with heart valves

In addition, clinicians combine the protocol with cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET). Having a patient wear a pulse oximeter and gas analyzer mask while they exercise on a treadmill or a bicycle can help define breathing problems as coming from the lungs or the heart, or both.

Each of these tests provides the patient-specific information required for a targeted care plan. Consequently, our cardiologists — and others across the country who perform the same tests — can provide more personalized care.

“These are precision diagnostics, so we can figure out how properly to refer people on to the wide variety of interventions we have available,” says Kirkpatrick. “I am honored to work at the place where Dr. Bruce laid the foundation.”