Backpack-size kidney-dialysis device wins ASN KidneyX prize

The CDI’s kidney-dialysis device prototype, is small and lightweight. A backpack-size kidney-dialysis device, conceived and being developed at the University of Washington Center for Dialysis Innovation (CDI), is one of six winners of a $650,000 prize in an international competition to create components and systems for artificial kidneys.

The awards were announced today by KidneyX, a public-private partnership of the American Society of Nephrology and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Through a series of cash competitions, KidneyX seeks to speed drug and device development to counter the steep global growth of kidney disease, now estimated to afflict 850 million people.

Jonathan Himmelfarb, left, and Buddy Ratner co-direct the Center for Dialysis Innovation.

Dr. Jonathan Himmelfarb, a professor of nephrology at he UW School of Medicine, accepted the award for the CDI, which he co-directs.

“This is our third win with KidneyX and the first iteration of the artificial-kidney prize,” Himmelfarb said. “There will be another phase of competition next year whose goal is an integrated system that works. Ultimately the idea is that one or more competitors will get novel systems commercialized and we’ll get these to patients to change their lives.”

The CDI is a collaboration of scientists and physicians at UW Medicine and UW Bioengineering. Himmelfarb said 30-some people are working on the CDI’s prototype artificial kidney, a device intended to free patients from thrice-weekly, hours-long visits to dialysis centers. The onerous regimen typically ends only when the patient receives a kidney transplant or dies.

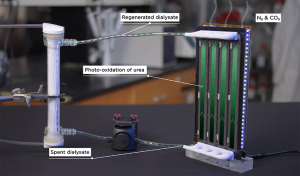

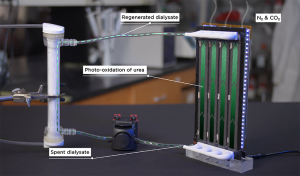

CDI scientists devised a process to recirculate dialysate, eliminating uremic toxins by converting them to odorless gases.

In this second phase of competition, KidneyX asked participants to devise a component that could be integrated into an artificial kidney system. Instead of developing just a component, CDI engineers are building a complete renal replacement machine.

Portability is a defining characteristic of the AKTIV kidney-dialysis device, shown here in prototype. Photos courtesy of the Center for Dialysis Innovation

Competitors’ essential challenge is miniaturization: At a dialysis center, the instruments weigh several hundred pounds, stand 5 feet tall, and go through gallons of water during every treatment. They are far from portable.

The CDI scientists hope to model the technology-enabled downsizing of the left ventricular assist device, which keeps blood flowing in people whose hearts have failed and who await transplant. In its initial iteration decades ago, the circulatory machine was console-size; today an implantable artificial heart is powered by a backpack-size pump and battery that users can take on a hike.

“That downsizing is quite analogous to our portable kidney machine,” said Buddy Ratner, CDI co-director and UW professor of chemical engineering and bioengineering. ‘The upside is that a patient with a wearable artificial kidney will get continuous dialysis, which we think will have great health benefits because it more closely emulates the natural organs’ filtering function.”

During hemodialysis, blood passes on one side of a semipermeable membrane; on the other side, fluid circulates, drawing toxins out of the blood. One striking advance of the CDI’s device is an eco-friendly way to dispose of the toxin-filled dialysate left after every patient-treatment session.

“Our breakthrough technology that we think will allow wearability and portability is the new approach to eliminating urea and other toxins from the dialysate,” Himmelfarb said. “Instead of having hundreds of liters of dialysate go down the drain, we have created a closed-loop system of a liter of dialysate that continuously recirculates while uremic toxins are removed and transformed into nitrogen and carbon dioxide – two colorless, odorless gases in the atmosphere.”

He credited that innovation to Bruce Hinds, a UW professor of materials science and engineering, and postdoc Guozheng Shao.

The CDI calls its artificial kidney system “AKTIV: Ambulatory Kidney to Increase Vitality.” It earned the group’s third KidneyX prize, following awards made in 2019 and in 2020.

Himmelfarb and Ratner have co-founded a company to license the AKTIV technology from the UW and commercialize it.

“Our goal is to have a device ready for clinical trials in two years. There are still a lot of steps to turn a proof-of-concept on the (research) bench into something we know will function safely and effectively,” Himmelfarb said.

CDI partner Northwest Kidney Centers is providing $15 million to fund novel ideas and technology that transform how patients experience blood-cleansing dialysis.

“This CDI’s artificial kidney prototype is an important step in advancing a truly innovative patient-centered approach to dialysis treatment,” said Rebecca Fox, CEO of Northwest Kidney Centers. “We are proud to support the efforts of this amazing team.”

Story by Brian Donohue courtesy of UW Medicine | Newsroom