New biomarker could one day help tailor immunotherapy for Merkel cell carcinoma

It's the cancer-fighting immune cells in a Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) patient's blood — not their tumor — that best predicts whether a certain type of immunotherapy will work, according to new work from two teams of scientists at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and the University of Washington School of Medicine.

The findings are a step toward the development of a clinical test that could someday guide MCC treatment.

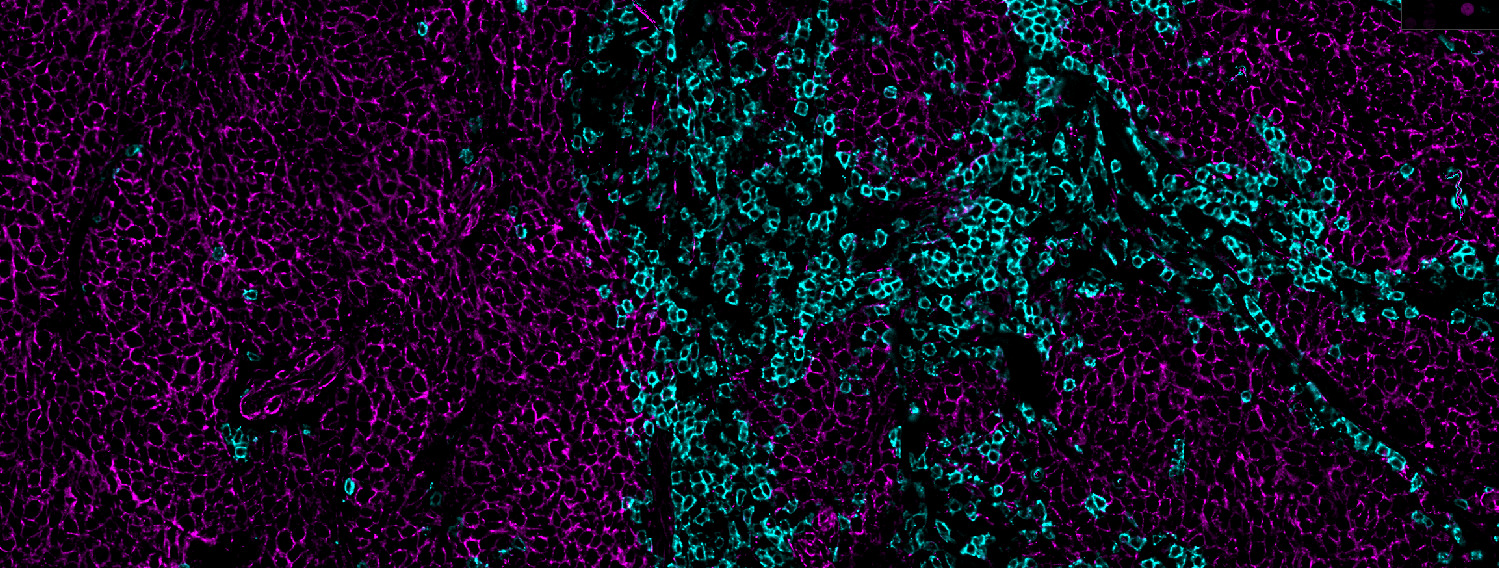

In back-to-back papers published in Cell Reports Medicine, the researchers showed that the frequency of circulating battle-ready anti-cancer immune cells act as a biomarker in patients with this aggressive skin tumor: MCC patients with higher levels in their blood are more likely to respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors, or ICIs.

Because these cells are the cells that ICIs help fight cancer, the results also suggest strategies scientists could use to improve patients’ chances of responding to ICIs.

Department of Medicine faculty and staff involved in the research include Drs. Aude Chapuis, associate professor, and Joshua Veatch, assistant professor (Hematology and Oncology), and Lichen Jing, research scientist, and Dr. David Koelle, professor (Allergy and Infectious Diseases).

Related Articles

- Circulating cancer-specific CD8 T cell frequency is associated with response to PD-1 blockade in Merkel cell carcinoma

- Merkel cell polyomavirus-specific and CD39+CLA+ CD8 T cells as blood-based predictive biomarkers for PD-1 blockade in Merkel cell carcinoma